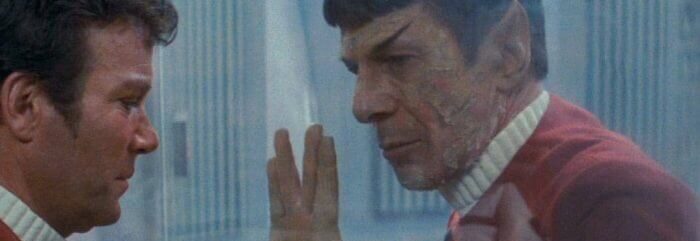

This post will certainly date me as I make a comparison to the classic Star Trek movies. At the end of Star Trek II, the iconic character Spock exposes himself to lethal amounts of radiation in order to repair the Starship Enterprise and allow it to escape a deadly explosion. After fleeing the explosion, the crew communicates with Spock during his dying moments as he is quarantined inside an engineering section. The commander of the ship, Admiral Kirk, is distraught at the imminent death of his friend, but Spock counsels him to not grieve, saying “it is logical; the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, or the one.”1

I feel that modern healthcare’s emphasis on statistical proof reflects this Vulcan logic, and I support it. It is absolutely imperative that we try to divine what treatments work and to what degree. Otherwise, we can’t really make tangible progress in improving patient’s lives. Statistical significance is a vital measurement for inferring that patients are receiving a higher level of benefit. It needs to be remembered that this significance, however, is dependent on the combined results of the group.

Notwithstanding the value of group studies, there are inherent issues with this system if the logic is applied incorrectly. For example, many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conclude with some sort of statement that a given treatment “appears to be effective,” “maybe more effective than _____ treatment,” or “did not perform better than placebo.” These are simplified statements of what statistical significance represents; that is, that there is a less than 5% chance of seeing a difference in effect this large or larger due to chance alone,2 among a group of people exposed to the conditions of the study.

Unfortunately, erroneous conclusions and practice patterns often abound with regard to statistical significance. Results from RCTs are improperly used to conclude that a given treatment never works, always works, or works only when a patient succumbs to the placebo effect. Additionally, it is often forgotten that even a “less effective treatment” will have “responders” that react very strongly to a given intervention. This shouldn’t be dismissed as a mere placebo. I believe it is a more fair and rational approach to consider a research study meeting statistical significance as an indicator of what is more likely to benefit a certain patient with a certain condition.

Interestingly, after Spock was brought back to life in Star Trek III, he learns that considering the needs of the one over the group, at times, is the more appropriate approach. Specifically, he discovers that his human colleagues acted against his Vulcan logic by endangering their lives and careers to save their friend.3 As human clinicians treating human patients, we should also attempt to balance how we practice by considering the results of group studies and applying them on an individual basis.

References:

1. Sallin, R. (Producer) & Meyer, N. (Director). 1982. Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. United States: Paramount.

2. Goodman, S. A Dirty Dozen: Twelve P-value Misconceptions. Semin Hematol 45:130-140.

3. Bennett, H. (Producer) & Nimoy, L. (Director). 1984. Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. United States: Paramount.